A Surgeon without Hands: The 50 Year Adventure of Dr. Marlys Witte

Dr. Marlys Witte is one of only a handful of surgeons without hands. Meaning, she’s been in the field of surgery almost her entire life, working alongside surgeons, completing surgical fellowships, conducting surgical research, and even teaching surgery clerkships. But she is not an operating surgeon.

As Dr. Witte explains it: Harvey Cushing, of course a great neurosurgeon who was technically superb, said someday there would be some leaders in surgery who didn’t have hands, meaning that surgery is a discipline beyond and in addition to the technical aspects of it. It deals with certain types of problems in patients, certain types of perspectives and attitudes that contribute to the care of patients who undergo surgery. So, I‘m one of a few faculty around the country who are professors of surgery who are not operating surgeons but are clinicians and see patients and do surgical research.

One of the founding members of the University of Arizona Department of Surgery, this year marks Dr. Witte’s 50th anniversary with the department. Training and mentoring medical students, women, and aspiring physicians; conducting groundbreaking research on the international stage; and helping to pioneer a new field of study are just a few of her many accomplishments.

The Beginning

If you asked Marlys Witte what she wanted to be when she grew up, a surgeon is the last thing she would have told you. Originally born in New York City and raised in Hackensack, NJ, down the block from what is now one of the largest medical centers in the country, she grew up in a family where a love of learning was encouraged and enjoyed many different subjects, including math, literature, and chess, in which she and her brother became involved on a professional level. When she attended college, she started out as a Russian major so she could translate chess books for her friends.

It wasn’t until she took a required course in zoology that Dr. Witte realized medicine was her calling: I thought that my mindset kind of liked messy, chaotic things that were mysterious and not well known. And therefore, I was more attracted to medicine, because patients and diseases were much more complicated, I thought, than things in the lab. And I was challenged by those. To be out in the unknown, I think that’s where challenge is made, the curiosity, the excitement.

Surgery in particular attracted her because it was the ultimate discipline of the unknown. Ignorance is my other theme: the things we know we don’t know, don’t know we don’t know, and the things we know but don’t, she said. And, as my husband

always said, surgery is the ultimate discipline of ignorance. It’s because the surgeon cuts out whatever the internist doesn’t understand. So, a surgeon can be very reflective when he or she operates that they‘re really operating on things that

we‘re ignorant about, because we would be preventing them, or we wouldn’t be cutting them out.

Camelot

In 1969, Dr. Erle Peacock, Jr., founder and original chair of the UArizona Department of Surgery, invited Dr. Witte and her husband, Dr. Charles Witte, to join as the second and third members of the department. They had met Dr. Peacock during their days as interns in Chapel Hill, NC. While they‘d never been to Tucson, the Drs. Witte visited the city and liked it and were excited about the prospect of starting a new department, so they agreed.

For several years, it was truly Camelot, Dr. Witte reflects. We had a real team, we were building things, we had a million dollars in research grants at a time where the rest of the medical school barely had a million dollars. A lot has changed, but I still think the department and faculty members, all of them, are very committed to teaching, which I think continues to distinguish the department.

One of the first female academic surgeons, Dr. Witte also became involved in mentoring other women physicians during this period. In the 1970s, she was part of the Women in Medical Academia Project, funded by the federal government to organize leadership workshops for women in academic medicine.

She remembers: Over those years, we trained tens of thousands of women in medicine, including minority women and foreign medical graduates, and they went on to develop their own workshops. I‘ve always had that commitment to underrepresented populations, you might say, and to mentoring women. Actually, the Women in Surgery section, which is one of the big specialty sections of the American College of Surgeons, started at our first leadership workshop. That began right here in Tucson at the Arizona Inn. It was a very exciting time in the beginning, because everyone was here; we were pioneering. We‘d left other institutions because we wanted something different.

The Medical Student Research Program (MSRP)

The theme of ignorance and the insatiable curiosity that drew Dr. Marlys Witte to surgery in the first place have also guided her approach to teaching students. In 1982, she was unanimously voted by the department heads of the College of Medicine and asked by the dean to direct the Medical Student Research Program (MSRP).

The MSRP provides funded opportunities for medical students to conduct research in anything from molecular to clinical projects. The program has since expanded to high school and college students, particularly those from underserved communities.

[The theme of ignorance] is what I try to bring to the students, why I‘m interested in and developed the MSRP. It’s so students can reignite the curiosity they had when they were kids. They can then explore things that nobody but them or their mentors may know or care about and have that feeling of discovery, rather than just having that every course is the same, every student gets the same exam, carbon-copy education. The experience should reflect the adventure that is medicine, where the patient comes along with you.

In fact, Dr. Witte has christened the summer portion of the MSRP program ’the Summer Institute on Medical Ignorance. In the spirit of continuous curiosity and discovery, she requires her students to keep Ignorance Logs, where they must write down three questions a day, whether related to their research or not. In the middle of the summer, students also participate in Failure Rounds, during which they present an aspect of their research that didn’t work.

’some of [the students] don’t like to have to put their unknowns down, said Dr. Witte. But most of them get on board, and some of them really get into it. Looking back on it, students who were reluctant to really question a lot realized they gained something. They gained something approaching patients; many of them gained something approaching life.

A Prolific Researcher

A fascination with the unknown naturally sparked a passion for research in Dr. Witte, especially in the field of lymphology, which was only first emerging when she started studying medicine. Her research has opened up an international forum and network of colleagues that she cites as one of the most exciting parts of her career.

A self-proclaimed lymphomaniac, Dr. Marlys Witte began studying lymphology with her husband, Charles, and their medical school mentors in the mid-60s. One of the most groundbreaking studies examined patients with heart failure or cirrhosis of the liver. These patients were experiencing immense swelling as a result of high venous pressure, causing an overproduction of lymph fluid. The research team found that, by simply draining the excess fluid, these patients improved significantly. For a while, the drainage was recognized as an official procedure, the costs covered by insurance companies.

Dr. Witte and her team further expanded this idea in the following years, discovering that they could, for example, take extra lymph from the failing right side of the heart and channel it into the left side, and the fluid accumulation would go away. Despite being well-tested and highly conclusive, the results of the study laid largely dormant for nearly 50 years, in part due to the simultaneously emerging field of transplantation.

Interest in this study was rekindled a couple years ago as Dr. Witte began to be called into pediatrics departments to look at infants displaying symptoms similar to those she had studied half a century ago. A surgeon from Wisconsin tried the procedure outlined in this paper officially called a thoracic duct to pulmonary vein or left atrial shunt on a terminally ill patient, saving the infant’s life. The procedure is now performed internationally by interventional radiologists who can complete it with minimal invasiveness.

The resurgence of this research after nearly 50 years has been a highlight of Dr. Witte’s career. She reflects, I was invited to this consensus meeting on lymphatic imaging. One of the leading cardiologists at this meeting, who was really a big name, put up a slide and he had the abstract of one of these papers I wrote 50 years ago, with my quotes highlighted like, ‘dr. Witte said this, Dr. Witte said that, Dr. Witte said that, and now we‘re doing this. So, to me, it was very exciting that he read the paper that I‘d written 50 years ago and that he analyzed it and it turned out to be applicable. I suppose only when you‘ve been around for 50 years can something like that happen.

Looking Back and Looking Forward

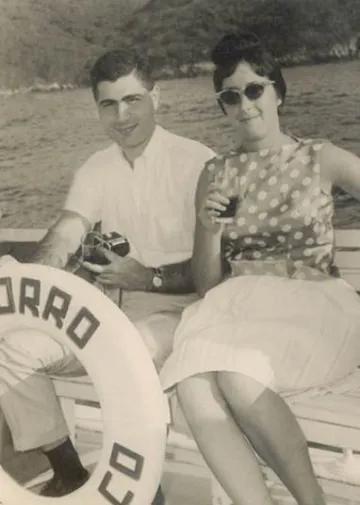

Reflecting back on her time with the department, Dr. Witte says it’s difficult to choose a favorite moment, but that working alongside her husband, the ongoing discovery, and the grassroots nature of academic surgery have been some of the most enjoyable parts of her career.

I like when teams work together in the operating room, not just operating but observing and discovering, she said. You have a high school student next to a professor, and so on. That kind of atmosphere we‘ve had very often.

She says the ultimate highlight, however, is watching from the wings while the things she helped build flourish: for example, watching two students from different backgrounds underrepresented in medicine, who may not have had opportunities in the medical field otherwise, present compelling, high-quality research.

Dr. Witte also remains active in research herself. After our call, she mentioned she was meeting virtually with colleagues from Genoa, Italy, to discuss the lymphatic system’s role in the spread of COVID-19 and how this information may be used to slow the spread of the virus.

Her parting words for aspiring surgeons ‘remain curious, and continue to ask questions,' every time you see a patient. My husband used to say, Always leave unsatisfied. Even when you‘ve done a perfect operation, always think of how it could be better. What don’t you know? I would say that’s really important.