Surgery and Native American Medicine

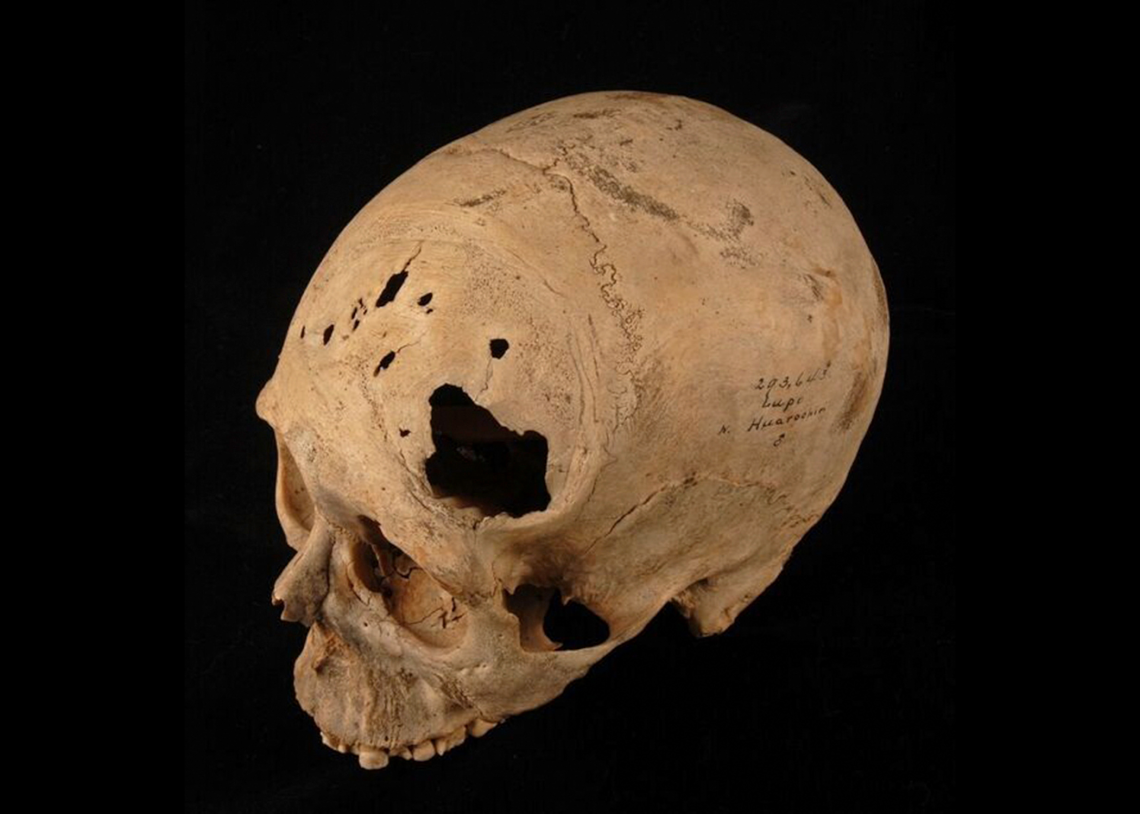

Cranium of adult male circa1000 1400 AD: It shows large area of scraping through outer table and diploë of frontal bone, with smaller openings through inner table. Fresh scrape marks and exposed diploë indicate death during or shortly after the operation. D. KUSHNER ET AL., WORLD NEUROSURGERY 114, 245 (2018)

Native American Heritage Month is celebrated every November to commemorate and recognize the present and past cultures, histories, technologies, and contributions of the original people of the Americas. In addition, we would like to recognize the many, often overlooked, innovations made by Indigenous tribes regarding medicine and the practice of surgery.

Syringes and Enemas

Alexander Wood is often credited with inventing the first hypodermic syringe in 1853. However, widespread evidence shows that Native Americans were using this kind of tool long before Wood’s version. Using material such as animal bladders and bird bones, Native Americans designed a syringe to inject medications and irrigate wounds. Larger versions of these tools were also used as enemas to treat constipation, diarrhea, and hemorrhoids as well as to administer ceremonial hallucinogenic drugs.

Suturing

Another surgical technique practiced by many tribes throughout history was suturing. North American Indians such as the Dakelh, Mescalero Apache, Dakota and Ho-Chunk primarily used sinew (and human hair and vegetable fibers) to suture wounds. Some South American tribes used a particularly innovative method a precursor today’s skin clips in which leaf-cutting ants pinched the edges of a wound together and then their heads were twisted off.

Anesthetics and Pain Management

Thanks to their early knowledge of pharmacology, many Indigenous tribes had humane and effective anesthetics that European doctors lacked.

For example, in addition to its uses as a pain reliever for lacerations, fractures, and snakebites, peyote has been used for thousands of years by tribes in what is now the southwestern U.S. and northern Mexico as a religious sacrament. (After many decades of the U.S. government trying to ban peyote use among Native Americans, a 1994 amendment to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 protected its use among Indigenous tribes.)

Likewise, Native peoples of the Virginia area used Jamestown weed, otherwise known as jimson weed, as an anesthetic both externally and internally.

Willow bark was another commonly used anti-inflammatory and pain relieving medicine. Salicin, the active ingredient willow bark produces, was crucial to the discovery of aspirin. It is also the precursor to salicylic acid, used today in many modern acne treatments.

Another common pain reliever used throughout the pre-Columbian Americas, and around the world, was capsaicin. In both the Aztec and Mayan empires, it was used to treat various conditions, including arthritis, stomach aches, skin rashes, and animal bites.

Trepanation

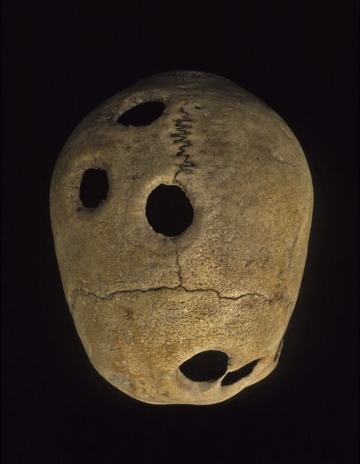

Cranium of an adult man from the Inca period that shows 5 healed trepanations. D. KUSHNER ET AL., WORLD NEUROSURGERY 114, 245 (2018)

Historically, Native Americans also performed certain surgical procedures with better outcomes than European and American physicians. Perhaps the most iconic illustration of this is trepanation, which is when a hole is drilled, cut, or scraped into the skull for medical purposes.

Trepanation has been performed for thousands of years all over the world, but one study suggests that Inca surgeons were particularly good at the procedure 80 percent of such operations were successful in pre-Columbian Peru, compared with only a 50 percent success rate among American Civil War procedures (at least 400 years later).

In the study, researchers examined more than 59 skulls that were believed to be from between 400 BCE to the mid-1500s CE all around Peru, including the capital of the Inca Empire, Cusco. The survival rates of the earliest patients were around 40 percent, but as time progressed, the technique and skill level of the Inca surgeons improved. Survival rates went up to between 75 and 83 percent during the height of the Inca empire (from the early 15th to 16th centuries).

The Inca’s later trepanation procedures benefited from continuous improvement in surgical techniques. Skulls had smaller holes due to less cutting or drilling and more careful grooving, helping increase survival rates. This practice of trepanation continued among the Incas until the 16th century when Spanish invaders destroyed the Inca Empire and made the practice illegal.

Trepanation was not the only successful surgical procedures Native Americans were able to perform. Indigenous peoples also practiced joint aspiration, debridement, and thoracentesis.

The history of Indigenous medicine throughout the Americas is largely overshadowed by Western influence, but that does not diminish the significance of their innovations over thousands of years and into today. As a land grant institution, it is vital for us to both honor the indelible Native American heritage in Arizona and, through partnership and collaboration, ensure that we are serving Indigenous communities across our education, research, and clinical programs.

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O'odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.